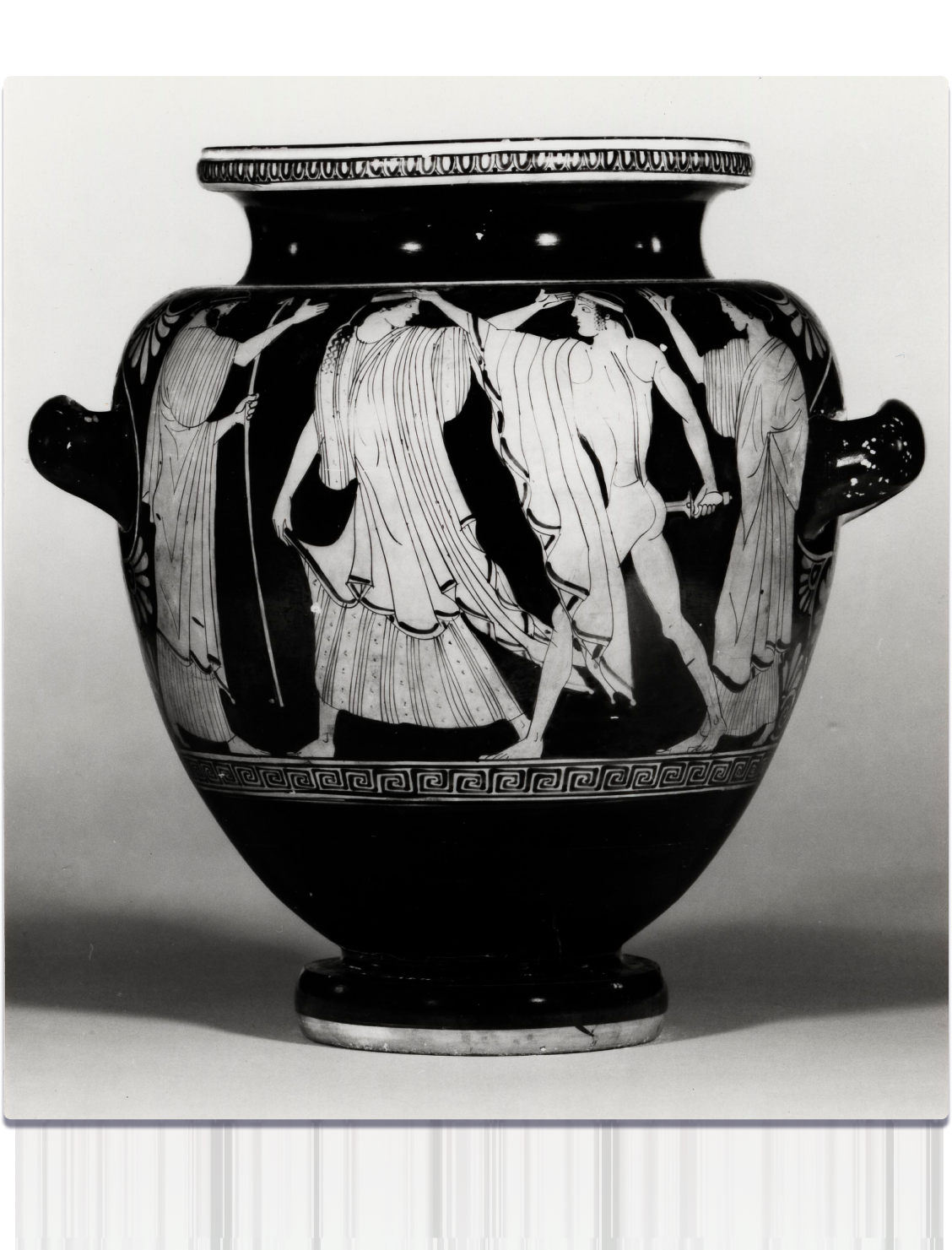

Identifying himself with the serpent, Orestes immediately concludes that he should kill his mother. For him, the dream is clear. For Clytemnestra, it takes more than three hundred verses to finally understand the meaning of her dream and the consequences that, unbeknownst to her, it will have on her future.

Orestes is about to kill his own mother. in a desperate attempt to stop him, Clytemnestra shows him her breast, the breast that the serpent in her dream suckled and wounded, thus mixing milk with blood. She asks Orestes to have mercy on the breast with which he used to be lulled to sleep, which he used to suckle milk that nourished him (ll. 896-898). However, this event was not enough for clytemnestra to begin to associate the action, her impending death and her dream. For clytemnestra, it was unimaginable that her own son could be the perpetrator of Agamemnon’s revenge as announced in her dream. As a mother, the one who gave Orestes life, nourished him with her milk, and cared for him as a child (mother-tokeus and mother-tropheus), matricide was an unconceivable thought.

Clytemnestra’s dream is not only prophetic in foreshadowing future events, but sets in motion a precise course of action. In this sense, it seems plausible to argue that the dream is a device that engineers the unfolding of murderous events. Without clytemnenstra’s dream, we would only have Agamemnon’s murder, and Orestes’ interpretation of his mother’s dream is instrumental to the subsequent developments of the plot. when the dream is told to him by the chorus, Orestes makes himself the serpent (ekdrakontotheis ego), even emphasizing “it’s me who kills her” (kteino nin). Thus, the plot requires Orestes’ embodiment of his mother’s unconscious to unfold. More importantly, the maternal unconscious designs Orestes’ existential path. a divine necessity to kill Clytemnestra is not sufficient for the murder to take place. In order to fulfill the divine injunction, Orestes must become the product of his mother’s unconscious. The son must act as an interpreter of the oneiric signs that, in turn, make him first a tragic subject of doubt, and then the emblematic matricidal son of Western literature.

Nearly a millennium later, in the early Christian context of late Antiquity, another famous scene in the Western literary tradition shows the interaction between a mother’s dream, an interpreting son, and divine intervention. Once again, this interaction plays a crucial role for the development of the male child’s life trajectory, but now it is the mother who finds no difficulty interpreting her dream. It is the famous scene of Monica’s dream in Augustine’s “Confessions” (Confessiones), written between 397 and 398 CE. In Book III, the confessant recounts a prophetic dream that God granted to his mother, who was consuming herself in the deepest sorrow over her son’s debased life and the death of his soul (Saint Augustine 1998, III, xi, 19):

Her vision was of herself standing on a rule made of wood. A young man came to her, handsome, cheerful, and smiling to her at a time when she was sad and “crushed with grief” (Lam. 1: 13). He asked her the reasons why she was downcast and daily in floods of tears — the question being intended, as is usual in such visions, to teach rather than to learn the answer. She had replied that she mourned his perdition. He then told her to have no anxiety and exhorted her to direct her attention, and to see that where she was, there was he also. When she looked, she saw him standing beside her on the same rule. How could this vision come to her unless “your ears were close to her heart” (Ps. 9B: 38/10A: 17)? You are good and all-powerful, caring for each one of us as though the only one in your care, and yet for all as for each individual.

the now converted Augustine knows that the dream came from God and can retrospectively see the true meaning of ‘standing together on the wooden rule’ (regula lignea), which he identifies as the rule of faith (regula fidei). but when his mother told him about the dream, Augustine attempted to interpret it (ego ad id trahere conarer) as meaning that she should hope to become like him. Monica, however, immediately rebutted this false interpretation (vicina interpretationis falsitate turbata) without the slightest hesitation: “The word spoken to me was not ‘Where he is, there will you be also’, but ‘Where you are, there will he be also’” (1998, III, xi, 20).

At that time, Augustine was too immersed in earthly desires to see his own future reflected in the dream. Illuminated by her faith, Monica did not fall prey to the opacity of the signs. She could read God’s prophetic messages and make predictions about her son’s future. As Paul Rigby remarks, she had a “deeper sense of time,” and her ability to use immediate sensations “to connect with their eternal meaning, to connect the many events recorded in “the Confessions”, events that from a confessional viewpoint, belong to the lost time of Augustine’s wandering, is the art of confession” (2015, 64). Her Skill seems to have given Monica a pivotal role in “the Confessions” and its temporality, well beyond that of pious mother and God’s mouthpiece: she was “the guardian of the (future) self-narration of her son, the depositary of the life-trajectory to which her son is called to adhere but to which he resists conforming” (Giusti 2022). Indeed, nine years of praying and weeping for him passed before Monica’s hope was to be fulfilled. In order to find himself on the wooden rule on which Monica was already standing, Augustine had to find her where she had always been, firm in her faith. This double movement of prospective conversion and retrospective examination, animates the autobiographical part of his confession.

In her famous 1977 essay on the representation of motherhood, “Stabat Mater,” which coincides with her own experience of maternity, Julia Kristeva claimed that, “Christianity is doubtless the most refined symbolic construct in which femininity, to the extent that it transpires through it — and it does so incessantly — is focused on Maternality” (1986, 161). In this complex construct, the ‘Mater Dolorosa’ becomes a particularly powerful figuration, of which the Virgin Mary obviously represents the archetype, and “Milk and tears” became the privileged signs of the ‘Mater Dolorosa’ who invaded the west beginning with the eleventh century, reaching the peak of its influx in the fourteenth” (173).

For Kristeva, what “milk and tears” have in common is that they are both metaphors for non-speech, of a “semiotics” that linguistic communication cannot account for; The Mother and her attributes, evoking sorrowful humanity and thus, becoming representatives of a “return of the repressed” in monotheism. They re-establish what is non-verbal and show up as the receptacle of a signifying disposition that is closer to so-called ‘primary processes”. (174)

Monica is not a full embodiment of the ‘Mater Dolorosa’ as described by Kristeva, but she seems to share certain traits with this powerful model (which will reach its full construction only centuries later) with her constant grieving and weeping for her son while also having faith in his future conversion.

Perhaps, one may even find a classical prefiguration of this vision of the maternal in Clytemnestra. not so much towards Orestes, but rather towards her daughter Iphigeneia in the first play of the Oresteia, “Agamemnon”. From Clytemnestra’s maternal point of view, an inviolable bond of consanguinity binds together the mother and her daughter: Iphigeneia is the exclusive fruit of her womb, odis philtate (Agamemnon, ll. 1417-1418).

For Clytemnestra, Iphigeneia’s violent death is a source of sorrow and immense grief; she mourns and weeps for her daughter: her “sweet flower, the shoot sprung from me, the sore-wept Iphigenia”(ll. 1525-1526; trans. Chesi). In Greek literature, mothers tormented by anguish and pain over the death of their children are capable of turning into monstrous or dreadful mothers: embodiments of the ‘mater monstruosa’. Clytemnestra is so consumed by her grief of the death of Iphigeneia, sacrificed at the hands of her own father, that she trespasses human bonds. When she kills her daughter’s father (her husband), she acts as the personification of the avenging goddess Erinys (Agamemnon, ll. 1432-1433). She becomes an avenging mother. This is seen In Euripides’ tragic play “Hecuba”, where Hecuba, the wife of King Priam of Troy, also embodies the model of a ‘mater dolorosa’ transformed into a ‘mater monstruosa’. After the fall of Troy, her youngest son Polydorus is sent to King Polymestor in Thrace. When she learns that her son has been killed, she plots a plan for revenge. during a visit by Polymestor to Troy, she blinds him and murders his two sons.

The Christian figuration of motherhood does not allow for this kind of vengeful excess. Nonetheless, it is likewise the intensity of her pain that allows Monica, who perceives the spiritual death of her son, to open herself to divine messages. Monica’s tears are a physical manifestation not only of inner suffering, but also of a prayer that God can hear and answer, as Augustine writes just before recounting the dream (III, xi, 19):

“You put forth your hand from on high” (Ps. 143: 7), and from this deep darkness “you delivered my soul” (Ps. 85: 13). For my mother, your faithful servant, wept for me before you, more than mothers weep when lamenting their dead children. By the “faith and spiritual discernment” (Gal. 5: 5) which she had from you, she perceived the death which held me, and you heard her, Lord. You heard her and did not despise her tears which poured forth to wet the ground under her eyes in every place where she prayed. You heard her.”

As Marina Warner points out, while the Virgin Mary “was innocent of the experience of sin and failure altogether, a figure like Mary Magdalene also strengthens the characteristic Christian correlation between sin, the flesh, and the female,” and Monica, along with her, “is one of the few not entitled ‘virgins’” among female saints (2016, 239). The fact that Monica is not without sin is crucial to her role in “the Confessions” as a precursor to the unfolding of God’s plan, and as living proof for his operations in human time.

In Book IX, just before recounting the death of the woman who gave birth to him in the flesh, and cared for his spiritual salvation, Augustine does not portray Monica as an inherently perfect servant of God. She had flaws, but with the help of God (and only secondarily of other people), she became a wise, modest, and patient wife, who was also able to eventually convert her violent husband to God, and become the mother that her son admired(IX, ix, 21): “That was the kind of person she was because she was taught by you as her inward teacher in the school of her heart,” writes Augustine.

Of her remaining earthly attachments, Monica will be completely free at the moment of her death, when she will have finally seen the full completion of her innermost desires, which coincide with God’s plans for her son. Then she will be able to detach herself even from even the “weakest” of human desires: to die and be buried on her own land next to her husband (IX, xi, 27).

Clytemnestra and Monica are two very different mothers, belonging to two very different cultural contexts and literary genres: the former a character in Aeschylus’ tragedy in classical Athens, the latter a real woman presented to us in the autobiographical writing of her son, on the threshold between classical antiquity and medieval Christianity.

Yet, the two dream scenes show traces of a peculiar treatment of the signs and symbols emerging from the maternal. Also, and perhaps more interestingly, they show how the interpretation of those signs prove to be decisive in shaping the life stories of the sons, and to the realization of the divine plans conceived for them.

Without Clytemnestra’s dream, Orestes would not commit matricide and therefore would not fulfill Apollo’s will. In her dream, Clytemnestra offers her breast to the baby-serpent and with it blood and milk; Orestes recognizes himself in the serpent and, when he murders his mother, turns into the very serpent suckling her breast.

Monica’s dream, granted by God as a response to her copious tears and prayers, shows evidence of God’s presence and operations in Augustine’s life (at a time when he was not yet ready to see them) and precipitates a major change that will occur years later. Augustine will have to position himself next to his mother on the wooden rule, on which Monica is already standing, and firmly embrace the rule of faith, an example his mother has offered him throughout his life.